Holistic hamstring strengthening in rehabilitation

Strengthening the hamstring muscles is an important aspect of sports rehabilitation both following hamstring muscle injury (HMI) but also following host of other injuries. HMIs are problematic in football and their rate of incidence in elite football is rising,1 The restoration of hamstring muscle strength following injury is essential for optimal return to sport and prevention of re-injury. Restoring hamstring muscle strength is also vitally important following other injuries such as anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. For example, deficits in hamstring muscle strength and particularly low knee flexor to knee extensor strength ratio are risk factors for re-injury. Kyritsis et al.2 showed a 10% reduction in the ratio upon return to sport after ACL injury was a 10-fold risk factor for re-injury.

Typically, there is a reductionist approach to hamstring muscle strengthening, in which researchers and clinicians recommend the popular Nordic hamstring curl exercise (NHE). Admittedly, it has excellent ease of use, low cost in terms of equipment and can be used with a partner with little technical skill and knowledge. There is also extensive evidence of its effectiveness in hamstring muscle injury prevention, with 60-85% reduction in hamstring muscle injuries when employing the full 10-week intervention.3,4 Greater eccentric hamstring strength can also off-set the increased risk of injury following previous injury or in older players.5

However, the NHE is not the only hamstring strengthening exercise, it may be limited in its effectiveness by only targeting the distal aspect of the knee flexors involving high levels of knee dominance.6 There is also a low adoption rate in elite sport teams,7 which may be due to high levels of soreness associated with this exercise and possible associated calf dysfunction, cramping and problems which can accompany this exercise. Additionally during rehabilitation, it is unlikely the correct exercise based on the intensity of the required voluntary activation. The NHE is a supramaximal exercise, highly eccentric in nature, involving full body weight and may not be appropriate for all patients, particularly those with a lower strength capacity and as such, their body weight may represent too much of an excessive load.

The importance of high speed running prior to return to sport

An often neglected fact is that high speed running provides a functional over-load of the hamstring muscle, explaining why 70% of hamstring muscle injuries occur during high speed running.8,9 Exposing athletes to increased weekly sprint distances (90-120 m above 95% maximum velocity) and exposures (6-10 sprints) during team based training has been shown to be protective of lower limb injuries10 and as such sprint running progressions should form a part of on-field rehabilitation practice prior to return to sport and also general prevention upon return to sport. It is essential to gradually increase exposure to high speed running and avoid sudden large increases in acute loading which may increase HMI risk.11

Exercise choices

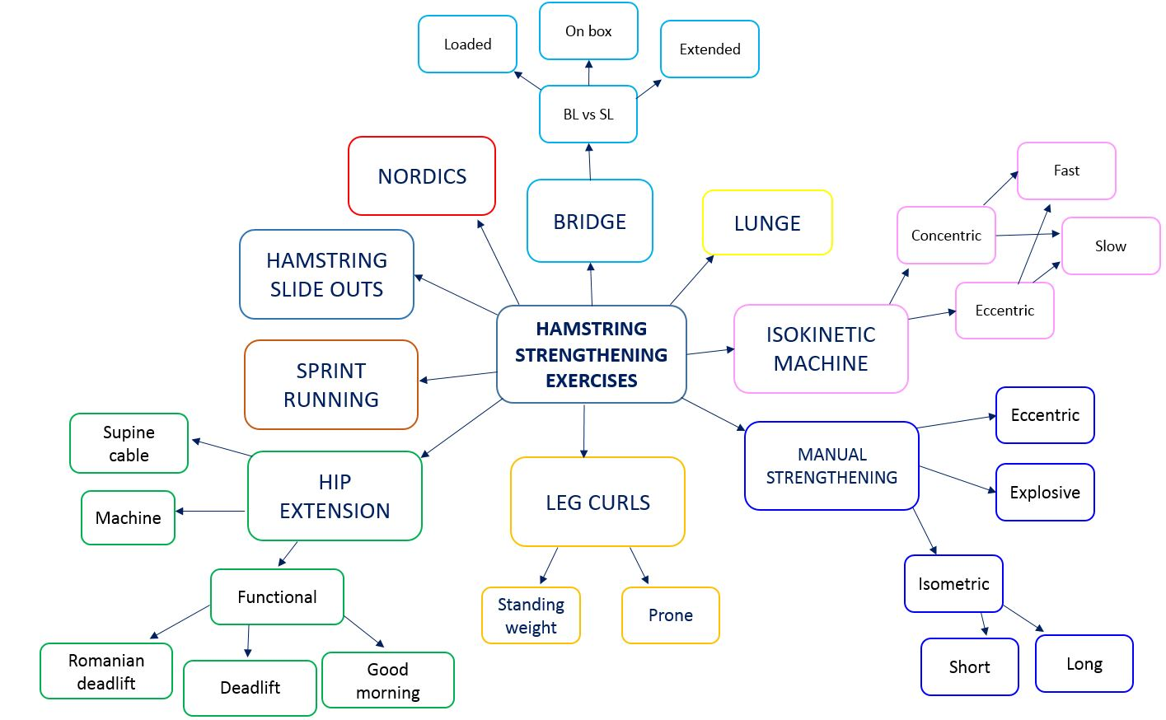

There are a range of exercise choices available to strengthen the hamstring muscles depending upon the current status of the patient/athlete (Figure 1). It is important to consider:

- Intensity of the exercise

- Balance of activation between constituent muscles of the hamstring

- Knee versus hip dominant

- Functionality of the exercises and required core control and stability

- Speed of contraction

- Contraction mode

Conclusion

Hamstring muscle strengthening is important in injury rehabilitation and prevention. There are various choices of exercises available and the program should ideally be holistic and reflect the needs of the patient/athlete.

Matt Buckthorpe BSc, MSc, PhD

Isokinetic Medical Group

Education & Research Department

References

- Ekstrand J, Waldén M, Hägglund M. Hamstring injuries have increased by 4% annually in men’s professional football, since 2001: a 13-year longitudinal analysis of the UEFA Elite Club injury study. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:731–7.

- Kyritsis P, Bahr R, Landreau P, et al. Likelihood of ACL graft rupture: not meeting six clinical discharge criteria before return to sport is associated with a four times greater risk of rupture. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Aug;50(15):946-51.

- Goode AP, Reiman MP, Harris L, et al. Eccentric training for prevention of hamstring injuries may depend on intervention compliance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015; 49: 349-356.

- Petersen J, Thorborg K, Nielsen MB, et al. (2011). Preventive Effect of Eccentric Training on Acute Hamstring Injuries in Men’s Soccer A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39 (11), 2296-2303.

- Timmons R, Bourne M, Shield A, et al. Short biceps femoris fascicles and eccentric knee flexor weakness increase the risk of hamstring injury in elite football (soccer): a prospective cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016; 50: 1524-35.

- Hegyi A, Peter A, Finni T, Cronin NJ. Region-dependent hamstrings activity in Nordic hamstring exercise and stiff-leg deadlift defined with high-density electromyography. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017 Nov 15. doi: 10.1111/sms.13016. [Epub ahead of print]

- Bahr R, Thorburg K, Ekstrand J. Evidence-based hamstring injury prevention is not adopted by the majority of Champions League or Norwegian Premier League football teams: the Nordic Hamstring survey. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1466-71.

- Woods C, Hawkins RD, Maltby S, et al. The Football Association Medical Research Programme: an audit of injuries in professional football- analysis of hamstring injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2004; 38: 36-41.

- Arnason A, Andersen TE, Holme I, et al. Prevention of hamstring strains in elite soccer: an intervention study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008; 18: 40-48.

- Malone S, Roe M, Doran DA, et al. High chronic training loads and exposure to bouts of maximal velocity running reduce injury risk in elite Gaelic football. J Sci Med Sport. 2017; 20:250-4.

- Duhig S, Shield AJ, Opar D, et al. Effectof high-speed running on hamstring strain injury risk. Br J Sports Med. 2016; 50: 1536-40.